What do you do when your castle becomes your prison? This homeowner used these words to describe how her feelings changed toward her home as her Multiple Sclerosis (MS) made it increasingly difficult for her to walk up three flights of steps from the street to the fourth floor.

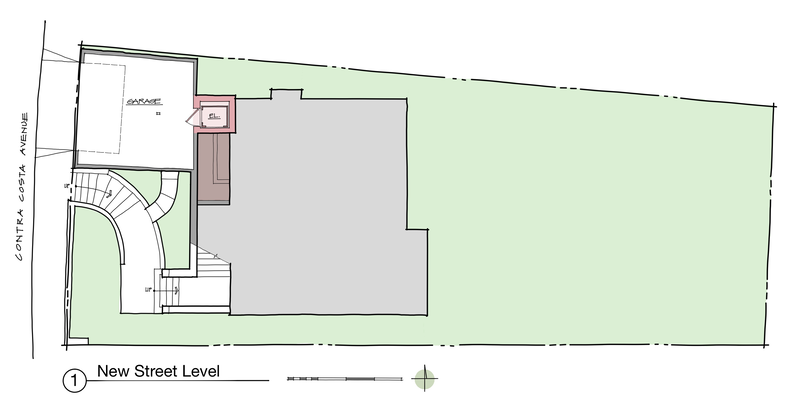

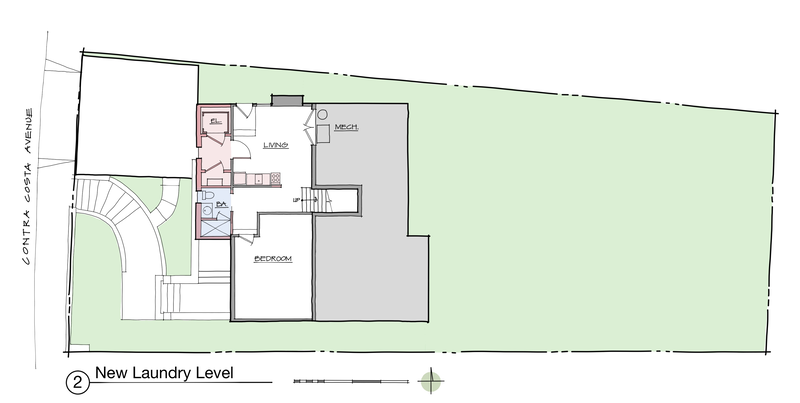

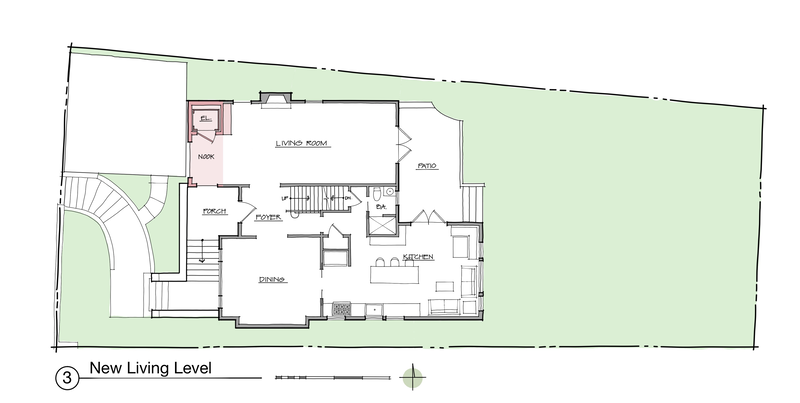

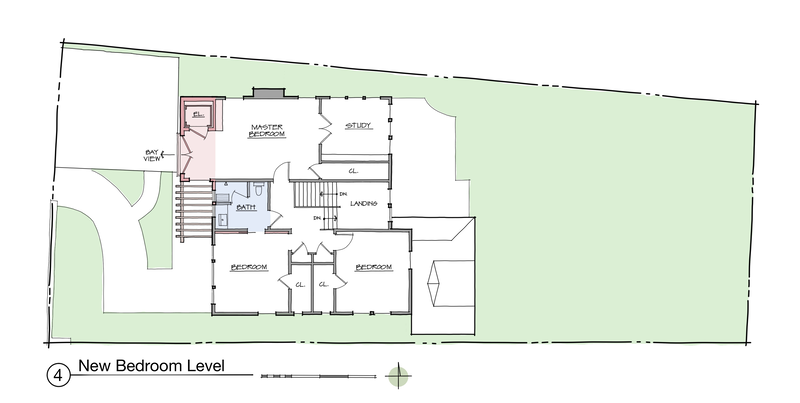

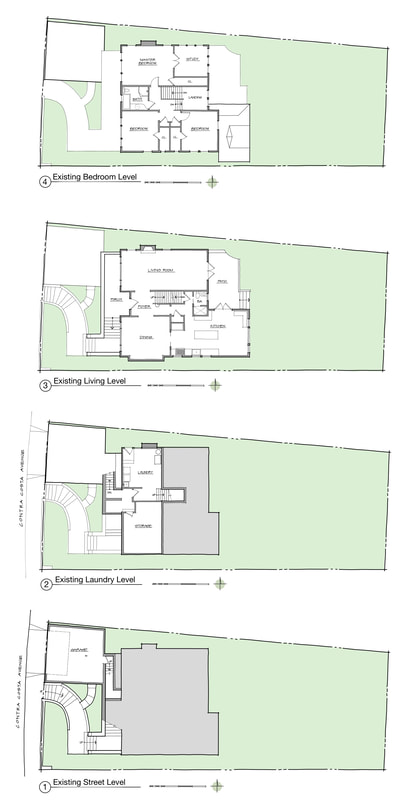

Perched up in the Berkeley Hills and overlooking the San Francisco Bay, this house served the family of three beautifully for 19 years, offering large rooms, an abundance of light, a sense of separation from the city, but still being just two blocks from a vibrant shopping district. It was a gracious and comfortable castle, and they had done a lovely kitchen addition just four years ago. When she contacted us, she was recently retired from law, mostly ambulatory using a walker, and still able to come and go from the house. Over the first six months of design and permitting, her MS accelerated, preventing lunches out with friends, shopping trips, and almost everything else. Her beloved house turned on her, imprisoning and isolating her. Two architects she spoke to before coming to us proposed a corner elevator connecting the garage to the three levels above. But both proposals were for a windowless, silo-like appendage that blocked windows and would always feel like they sacrificed the house to be able to stay in it; a Band-Aid approach that forgot about good design. The Hippocratic Oath instructs doctors to “do no harm” as they help patients. A band-aid silo would have harmed the integrity of this house and reduced the owners’ enjoyment of and affection for it. Instead, we took a more holistic approach, considering the entire house, and asking about the owner’s lifestyle. We learned about parties to watch July 4th fireworks from their high perch, and about the abrupt feeling of entry on the existing too-flat wall. We learned they anticipated a caregiver in the future, but wanted to maintain their private space. For a future live-in caregiver we created an accessory dwelling unit out of the laundry space. And we cleverly rearranged the small master bathroom to make a wheelchair-friendly space that didn’t eat into adjacent rooms. Rather than grafting an elevator on, we incorporated it into a larger addition, creating a friendly nook that on the two upper floors and an exterior shape that, combined with a new arbor to create a better entry experience, echoes the stepping of the existing stair wall; it is an architectural composition. The geometry, shadows, and rhythms get compliments from people walking by. None of them think it’s a project born of accessibility needs - they just see a beautiful addition and improvement to the home. For a person with a disability, dealing with people’s changing perceptions of them, with probing stares in public as they struggle with a two-narrow door or too-high checkout counter, is tiring and reminds them of what they can’t do rather than what they can. So creating a home that that doesn’t suffer harm in the process of becoming more usable, and mainly speaks of beauty and elegance, is a perfect outcome. Now, rather than being her castle prison, it is her liberator, her castle, and her friend once again. Team: Architect: Erick Mikiten, Rachael Koffman, Dewi Bleher - Mikiten Architecture General Contractor: Nick Silberman - Carlen & Co., Berkeley |