The Edge of Nature

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, tofront only the essentialfacts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when Icame to die, discover thatihad not lived.

—Henry David Thoreau, Walden

—Henry David Thoreau, Walden

CENTRAL TO WHEELCHAIR ACCESS iS the fund a- mental issue of access to nature. Thoreau also wrote that “Our lives need the relief of the wilderness where the pine flourishes and the jay still screams.” Such relief is available at shoreline sites near populated areas along the San Francisco Bay. These places offer opportunities to move from an urban to a natural environment. They transform the constructed landscape produced by reason ing minds to the more enduring landscape beyond. In the gridded streets of the city we are enmeshed in a societal structure. Na ture’s open spaces and irregularity break down this rigid framework, liberating us to encounter the environment on our own terms rather than on those of a developer or city planner. Experiences in nature can result in a new personal and professional point of view.

My architectural training influences my perception of environments as individually calculated structures that do not necessarily work with each other. But in recent shoreline explorations, I appreciated causal interactions between plants and animals I encountered. I began to see the world through the eye of an individual rather than the eye of an architect. I enjoyed this liberation on challenging paths more than along manicured paved roads. Experiences in nature are physical encounters. We should be able to engage a steep, rocky slope or a sandy beach rather than having to settle only for easily crossed flat terrain.

The fringe of ocean that slips over the sandy edge of land or pounds against its rocky border is a place of dramatic change. Whether the land is flat beach or sheer cliff, it becomes horizontal along the margin of the Pacific Ocean. The ability to enjoy that con trast firsthand is essential to the full appre ciation of both elements. But access for wheel chair riders to that convergence of water and land is emblematic of many other disability access problems; in everyday settings we can often get close to a goal, but are prevented from reaching it by one little staircase or, more crucially, a narrow restroom door.

There are places along the coast, however, where bodily contact with nature is possible for the wheelchair rider, where we can enter the water unassisted on tidal ramps or forge our way across rough terrain where nature is within arm’s reach. These experiences allow us to begin to realize the larger connectivity of the body and spirit between man and nature.

With the specific issue of wheelchair ac cess and the broader concern of appreciating nature in mind, I traveled the coastline and bay edge from the urban Santa Cruz Board walk to the Point Reyes wilderness on as signment for California Waterfront Age in search of places that provide the best access to the undulating line between the land and the sea.

My architectural training influences my perception of environments as individually calculated structures that do not necessarily work with each other. But in recent shoreline explorations, I appreciated causal interactions between plants and animals I encountered. I began to see the world through the eye of an individual rather than the eye of an architect. I enjoyed this liberation on challenging paths more than along manicured paved roads. Experiences in nature are physical encounters. We should be able to engage a steep, rocky slope or a sandy beach rather than having to settle only for easily crossed flat terrain.

The fringe of ocean that slips over the sandy edge of land or pounds against its rocky border is a place of dramatic change. Whether the land is flat beach or sheer cliff, it becomes horizontal along the margin of the Pacific Ocean. The ability to enjoy that con trast firsthand is essential to the full appre ciation of both elements. But access for wheel chair riders to that convergence of water and land is emblematic of many other disability access problems; in everyday settings we can often get close to a goal, but are prevented from reaching it by one little staircase or, more crucially, a narrow restroom door.

There are places along the coast, however, where bodily contact with nature is possible for the wheelchair rider, where we can enter the water unassisted on tidal ramps or forge our way across rough terrain where nature is within arm’s reach. These experiences allow us to begin to realize the larger connectivity of the body and spirit between man and nature.

With the specific issue of wheelchair ac cess and the broader concern of appreciating nature in mind, I traveled the coastline and bay edge from the urban Santa Cruz Board walk to the Point Reyes wilderness on as signment for California Waterfront Age in search of places that provide the best access to the undulating line between the land and the sea.

A Point of View

My first encounter with the dramatic California coastline was during a seven-month internship at an architectural firm in Santa Monica. That water front landscape is more commercially ma nipulated than many Bay area waterfronts, but significant access points exist. Marina Del Rey’s tidal ramp and lender wheelchair program for going into the salt water is one successful example.

This research project allowed me to ex plore the coastline in a methodical way. Sustained observation such as this reveals the perpetual essence of nature. I felt a com radeship with the naturalist John Muir, who wrote: “It is always the sunrise somewhere; the dew is never all dried at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is forever rising.”

Park brochures and the California Coastal Commission’s California Coastal Access Guide are good sources of basic information for the Pacific coastline. However, the book excludes bay waterfronts from its discussion, and some entries in the latest edition, published in 1983, are out of date rare insufficiently detailed to be of much use.

A wonderfully exhausting six-mile wheel chair trip along the East Bay can reveal sev eral faces of the Hayward Regional Shore line. At its northern edge, San Leandro’s Marina Park has a winding asphalt path that connects many paved picnic table and barb e cue areas. The park’s large open space is often filled with people throwing Frisbees, playing baseball, and flying kites. Nearby, a smooth, slightly rolling one-mile asphalt jogging loop is a convenient exercise course.

Another asphalt path leads south across a bridge and along the shore for one and a quarter miles before changing to dusty dirt and crushed rock. It extends across a pedes trian bridge over the San Lorenzo Creek and eventually reaches the staging area at Grant Avenue. The degradation I found here was disappointing, signaling the critical condi tion of our shoreline.

From Grant Avenue the path connects to ones that originate at the park office at Win- ton Avenue and the Hayward Shoreline Inter pretive Center off Highway 92 at the south ern end of the Regional Shoreline.

Moving along the area’s mud flats, I be gan to understand how they changed with the weather. Sometimes they are cold, barren landscapes across which wicked winds fly off the bay waters. Other times they are vi brant, expansive landscapes full of life, where birds with long, thin, nerve-tipped bills probe into the ooze and where ground squirrels and hares rush across the path around you. All these are part of the wetlands where two-thirds of our coastal fish and shellfish spend part of their lives.

The Interpretive Center is a wonderful and accessible station for learning to appre ciate even the less dramatic areas of the bay. Once we realize that fill and development has diminished the bay to half the size it was in 1850, we can understand and cherish these remnants of an ecosystem that was previ ously much more diverse.

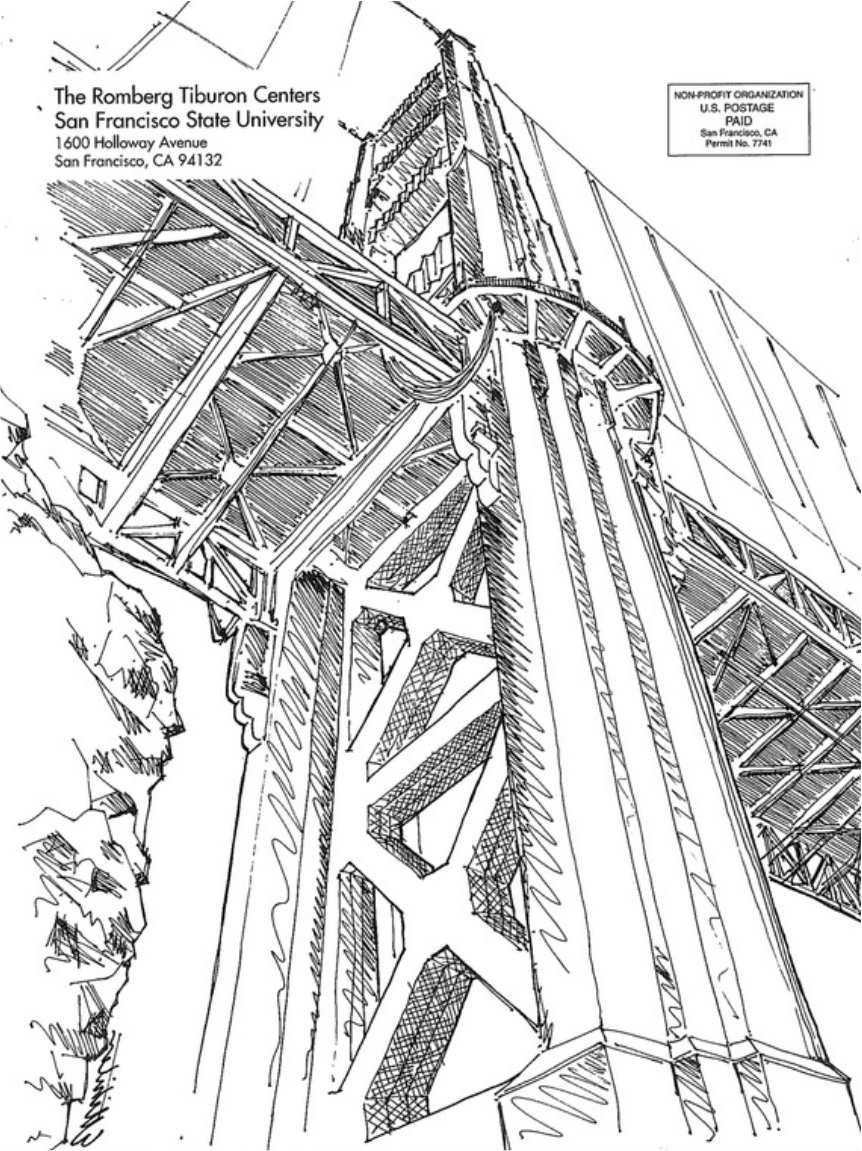

In time we discover special places that allow us to appropriate something in the public domain. The experience of being alone underneath the Golden Gate Bridge or mak ing a long trek out a dusty back trail are intimate encounters that let us adopt public places as our own. Exploration off the beaten path reveals these places that are so impor tant to the individual enjoyment of nature.

Fort Point, on the San Francisco side of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, is archetypical of the best of the Bay area urban waterfront. It offers a contrast between the drama of water and land and that of the human built environment. There are reserved parking spaces and accessible restrooms located periodically along the bay from the fort to the South Beach Marina. You can plot out an exercise routine—depending on time and stamina—to confront the hill between Fort Mason and Aquatic Park or the wide open spaces along Marina Green. Or you might plan a casual stroll out to the point to contemplate the dramatic landscape where enormous tankers pass below the Golden Gate Bridge, which rises above the blocky fort building At sunset, from this spot below the massive rust-colored girders of the bridge, looking southeast toward the City, you see the light-colored buildings glow with the reddening light from the setting sun, radiant against the foreground of Italian stone pines along the roads incised in the nearby cliffside.

Elsewhere around the Golden Gate, such as at Fort Funston, there are more natural areas that display only remnants of past human interventions. A number of aban doned forts and batteries are accessible to wheelchairs and often have parking nearby. The ruin-like concrete shell of Fort Funston’s Battery Baker is dark and ominous. Broken bottles and charred floors indicate a noctur nal use of these places by people who are gone in the daytime. Light that finds its way mis quickly absorbed by the shadows. Echoes rebound off smooth, hard walls covered with graffiti about war. These graffiti and the debris left behind by the anonymous visitors form a subtext that, in the cold darkness of the battery chambers, provides a sobering backdrop to the objective historical signage at the beginning of the trails leading you here.

This research project allowed me to ex plore the coastline in a methodical way. Sustained observation such as this reveals the perpetual essence of nature. I felt a com radeship with the naturalist John Muir, who wrote: “It is always the sunrise somewhere; the dew is never all dried at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is forever rising.”

Park brochures and the California Coastal Commission’s California Coastal Access Guide are good sources of basic information for the Pacific coastline. However, the book excludes bay waterfronts from its discussion, and some entries in the latest edition, published in 1983, are out of date rare insufficiently detailed to be of much use.

A wonderfully exhausting six-mile wheel chair trip along the East Bay can reveal sev eral faces of the Hayward Regional Shore line. At its northern edge, San Leandro’s Marina Park has a winding asphalt path that connects many paved picnic table and barb e cue areas. The park’s large open space is often filled with people throwing Frisbees, playing baseball, and flying kites. Nearby, a smooth, slightly rolling one-mile asphalt jogging loop is a convenient exercise course.

Another asphalt path leads south across a bridge and along the shore for one and a quarter miles before changing to dusty dirt and crushed rock. It extends across a pedes trian bridge over the San Lorenzo Creek and eventually reaches the staging area at Grant Avenue. The degradation I found here was disappointing, signaling the critical condi tion of our shoreline.

From Grant Avenue the path connects to ones that originate at the park office at Win- ton Avenue and the Hayward Shoreline Inter pretive Center off Highway 92 at the south ern end of the Regional Shoreline.

Moving along the area’s mud flats, I be gan to understand how they changed with the weather. Sometimes they are cold, barren landscapes across which wicked winds fly off the bay waters. Other times they are vi brant, expansive landscapes full of life, where birds with long, thin, nerve-tipped bills probe into the ooze and where ground squirrels and hares rush across the path around you. All these are part of the wetlands where two-thirds of our coastal fish and shellfish spend part of their lives.

The Interpretive Center is a wonderful and accessible station for learning to appre ciate even the less dramatic areas of the bay. Once we realize that fill and development has diminished the bay to half the size it was in 1850, we can understand and cherish these remnants of an ecosystem that was previ ously much more diverse.

In time we discover special places that allow us to appropriate something in the public domain. The experience of being alone underneath the Golden Gate Bridge or mak ing a long trek out a dusty back trail are intimate encounters that let us adopt public places as our own. Exploration off the beaten path reveals these places that are so impor tant to the individual enjoyment of nature.

Fort Point, on the San Francisco side of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, is archetypical of the best of the Bay area urban waterfront. It offers a contrast between the drama of water and land and that of the human built environment. There are reserved parking spaces and accessible restrooms located periodically along the bay from the fort to the South Beach Marina. You can plot out an exercise routine—depending on time and stamina—to confront the hill between Fort Mason and Aquatic Park or the wide open spaces along Marina Green. Or you might plan a casual stroll out to the point to contemplate the dramatic landscape where enormous tankers pass below the Golden Gate Bridge, which rises above the blocky fort building At sunset, from this spot below the massive rust-colored girders of the bridge, looking southeast toward the City, you see the light-colored buildings glow with the reddening light from the setting sun, radiant against the foreground of Italian stone pines along the roads incised in the nearby cliffside.

Elsewhere around the Golden Gate, such as at Fort Funston, there are more natural areas that display only remnants of past human interventions. A number of aban doned forts and batteries are accessible to wheelchairs and often have parking nearby. The ruin-like concrete shell of Fort Funston’s Battery Baker is dark and ominous. Broken bottles and charred floors indicate a noctur nal use of these places by people who are gone in the daytime. Light that finds its way mis quickly absorbed by the shadows. Echoes rebound off smooth, hard walls covered with graffiti about war. These graffiti and the debris left behind by the anonymous visitors form a subtext that, in the cold darkness of the battery chambers, provides a sobering backdrop to the objective historical signage at the beginning of the trails leading you here.

South of San Francisco, Natural Bridges in Santa Cruz is an example of how focus is continued inland from the actual coastline in places that are part of the park property. Monarch butterflies roost in the tall eucalyp tus here from early October to March. An extensive ramp system allows access to the gully where the monarchs perch. The ramp terminates in a wooden walkway that con nects to a three-level viewing platform. Only the lowest level is wheelchair accessible, although the other levels easily could have been made so. Two steps down from the wooden walkway prevent wheelchair access to a dirt path. The path becomes impassible by wheelchair in a few hundred yards, but contact with the ground should have been incorporated into the design. It is difficult to comprehend the logic of a ramp that takes a wheelchair rider down about 40 feet only to be kept from the ground by two 7-inch steps.

The visitors’ center at the top of the ramp is inaccessible because of two steps up to its entry door. And the fine sand of the nearby beach has no accommodation for wheelchair access. In the aggregate, this is a place to which some attention has been paid and a large effort has been made to provide wheel chair access, but a few issues small in scale but large in significance have been over looked.

bike and jogging path follows West Cliff Drive from Natural Bridges to the Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf, the longest public drive- on pier on the West Coast. From the wharf one can fish and look back to the Santa Cruz Boardwalk. Teeming with people, it looks like a colorful stage set displayed against the backdrop of the mountains and the fore ground of the beach and ocean. A temporary access ramp to the beach near the wharf is in the works, and two permanent access points to the beach in the wharf area are being planned for the near future.

The visitors’ center at the top of the ramp is inaccessible because of two steps up to its entry door. And the fine sand of the nearby beach has no accommodation for wheelchair access. In the aggregate, this is a place to which some attention has been paid and a large effort has been made to provide wheel chair access, but a few issues small in scale but large in significance have been over looked.

bike and jogging path follows West Cliff Drive from Natural Bridges to the Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf, the longest public drive- on pier on the West Coast. From the wharf one can fish and look back to the Santa Cruz Boardwalk. Teeming with people, it looks like a colorful stage set displayed against the backdrop of the mountains and the fore ground of the beach and ocean. A temporary access ramp to the beach near the wharf is in the works, and two permanent access points to the beach in the wharf area are being planned for the near future.

The Guidebook

I experienced these places in an Everest&Jermings Ultra Lite Premier—a fold able manual chair. I conferred with the user of an electric wheelchair to have a broader base for characterizing the conditions I encountered, but because information required for definitive access knowledge varies with every kind of disability and every short of wheelchair, the guidebook takes a descriptive approach rather than an ascriptive "yes" or "no" approach.