The way I look at it, if we exactly meet the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and California Building Code (CBC) minimums in our designs, we’re barely avoiding “breaking the law”. And with that “perfect” code-compliant design, one small mistake in the field and we’re losing money and sleep solving problems in construction administration.

That’s why I advocate Code Plus design. Give an extra few inches as a safety margin and you’ll be doing your client, the contractor, and yourself a favor!

The code and the ADA are minimum standards based on extensive negotiations between people with disabilities

and building owners associations and big developers. Guess whose agenda is better represented in the docu- ments we’re following?

Here are three ideas for you to take to the street (well, parking lot) in your projects. They will make the lives of your users much better - with barely any impact on square footage and cost.

1. Access Aisle Size

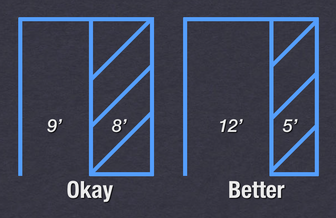

Here’s an easy one: CBC 11B-502.2 Allows van spaces to be 9 feet wide with an 8 foot access aisle or 12 feet wide with a 5 foot access aisle. Either way, it's 17 feet total width, but one is better than the other.

That’s why I advocate Code Plus design. Give an extra few inches as a safety margin and you’ll be doing your client, the contractor, and yourself a favor!

The code and the ADA are minimum standards based on extensive negotiations between people with disabilities

and building owners associations and big developers. Guess whose agenda is better represented in the docu- ments we’re following?

Here are three ideas for you to take to the street (well, parking lot) in your projects. They will make the lives of your users much better - with barely any impact on square footage and cost.

1. Access Aisle Size

Here’s an easy one: CBC 11B-502.2 Allows van spaces to be 9 feet wide with an 8 foot access aisle or 12 feet wide with a 5 foot access aisle. Either way, it's 17 feet total width, but one is better than the other.

Why? Because wide aisles are just too inviting for other drivers, and this happens:

So stick with the narrow five foot aisle, and give the remaining three feet to the van space itself.

2. Number of Van Accessible Spaces

I recently had to use an electric wheelchair for four months, and rented a van with a ramp. I was blown away to discover how many places I couldn’t deploy the ramp. Trees, bushes, signs, bike racks, and newspaper boxes

made many street spaces impossible. Regular accessible stalls with five foot access aisles often wouldn’t work, and I’d circle parking lots for 20 minutes until a usable van space opened up, or just give up and drive away.

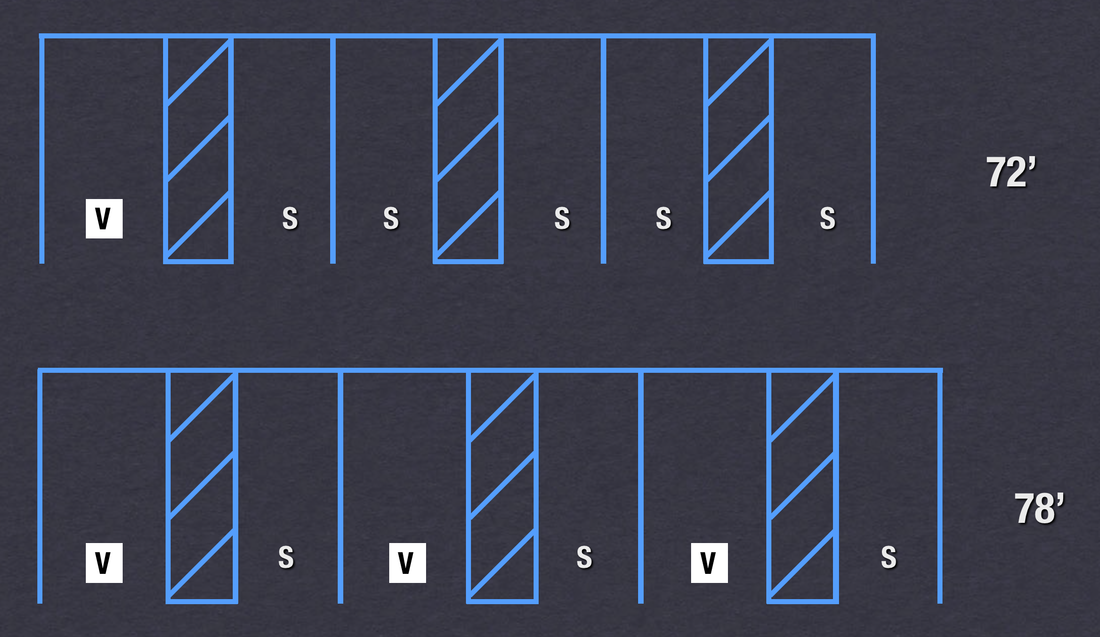

So...what if we made EVERY accessible space left of an access aisle a van space rather than a regular space? Surprisingly, in a parking lot with 200 spaces, that would add only six feet to the lot:

2. Number of Van Accessible Spaces

I recently had to use an electric wheelchair for four months, and rented a van with a ramp. I was blown away to discover how many places I couldn’t deploy the ramp. Trees, bushes, signs, bike racks, and newspaper boxes

made many street spaces impossible. Regular accessible stalls with five foot access aisles often wouldn’t work, and I’d circle parking lots for 20 minutes until a usable van space opened up, or just give up and drive away.

So...what if we made EVERY accessible space left of an access aisle a van space rather than a regular space? Surprisingly, in a parking lot with 200 spaces, that would add only six feet to the lot:

This shows the CBC Chapter 11B requirement for one van space per six required accessible parking spaces (it’s one per eight for housing under Chapter 11A).

In a double-loaded lot of about 55,000 SF, that’s only 108 SF of added space. I defy anyone to show me a 55,000 SF lot that I can’t squeeze another 108 SF out of. Put another way, that’s a unnoticeable 0.02% difference in most people’s experience, and a 100% better experience for people who need these spaces.

3. Number of Accessible Spaces

Imagine you have a green car and drive into a 200-space lot, but only 12 spaces are for green cars. There are 60 spaces empty around the lot, but all the green-car spaces are taken, and you can’t park anywhere. Wouldn’t that be dopey? Completely - and that’s what it feels like to people who need the accessible spaces. But this is easy to fix...

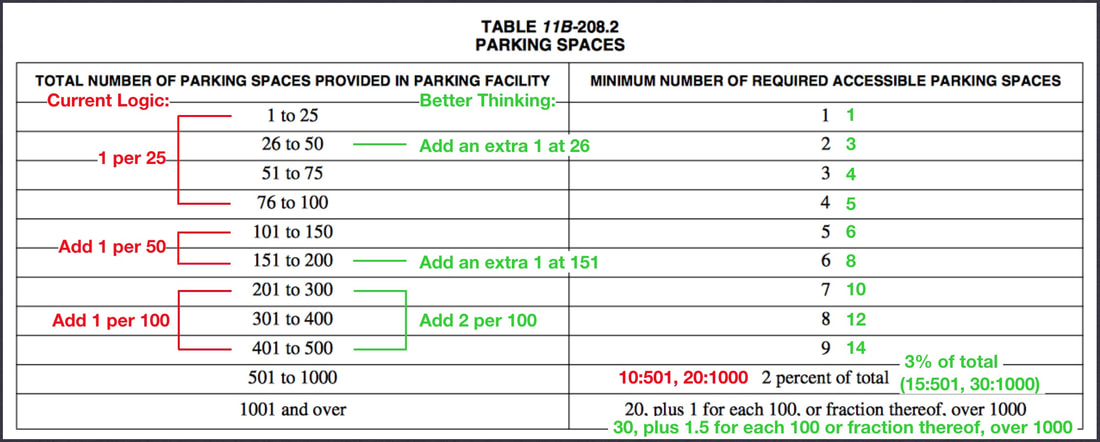

The CBC sets the required number of accessible spaces in Table 11B-208.2, based on total spaces. Here are the code numbers in red and black, with my suggestions in green. These are tiny changes, but will offer huge im- provements in real-world usability:

In a double-loaded lot of about 55,000 SF, that’s only 108 SF of added space. I defy anyone to show me a 55,000 SF lot that I can’t squeeze another 108 SF out of. Put another way, that’s a unnoticeable 0.02% difference in most people’s experience, and a 100% better experience for people who need these spaces.

3. Number of Accessible Spaces

Imagine you have a green car and drive into a 200-space lot, but only 12 spaces are for green cars. There are 60 spaces empty around the lot, but all the green-car spaces are taken, and you can’t park anywhere. Wouldn’t that be dopey? Completely - and that’s what it feels like to people who need the accessible spaces. But this is easy to fix...

The CBC sets the required number of accessible spaces in Table 11B-208.2, based on total spaces. Here are the code numbers in red and black, with my suggestions in green. These are tiny changes, but will offer huge im- provements in real-world usability:

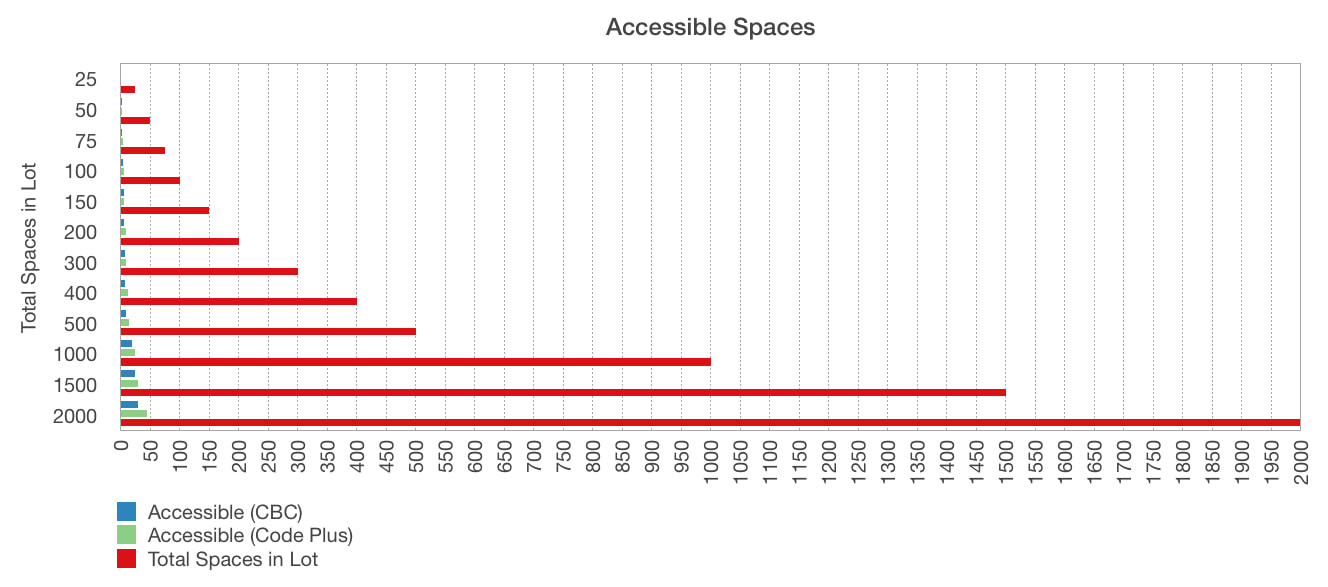

Here’s a graph of these changes, showing what a minute change this is:

Many of the accessibility numbers in the code were established in the 1970’s and 1980’s (with some dating back to first ANSI A117.1 of 1959), when the percentage of people over 70 was about half of what it is today...and that number is in the process of doubling between 2010 and 2030.

Add to that the fact that many people with disabilities were stuck in their homes due to lack of today’s advanced mobility aids and the lack of an accessible public environment (not to mention many people being institutionalized), and it’s quickly clear that these numbers need to be updated. It will take a long time for the glacial ADA and building code update processes to catch up.

In the mean time, it’s up to us to up the ante and create better places that reflect the reality of what the population needs. If we don’t do it, who will?

Add to that the fact that many people with disabilities were stuck in their homes due to lack of today’s advanced mobility aids and the lack of an accessible public environment (not to mention many people being institutionalized), and it’s quickly clear that these numbers need to be updated. It will take a long time for the glacial ADA and building code update processes to catch up.

In the mean time, it’s up to us to up the ante and create better places that reflect the reality of what the population needs. If we don’t do it, who will?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed