It happened again. I recently got an email in which the sender wrote “tow the line”. Then, minutes later, someone asked me why the code has maximum toe clearance dimensions. Let’s clear up both toe problems once and for all.

| First and more importantly (bad grammar is so irksome, isn’t it?), it’s “toe the line”. Don’t confuse it with nautical tow lines…it’s about feet. The phrase originated with soldiers lining up in the military or runners in track and field events, where officials would call out “Toe the line!” to get the runners ready. Either way, it’s the digits of the feet, lined up in a row, like this: |

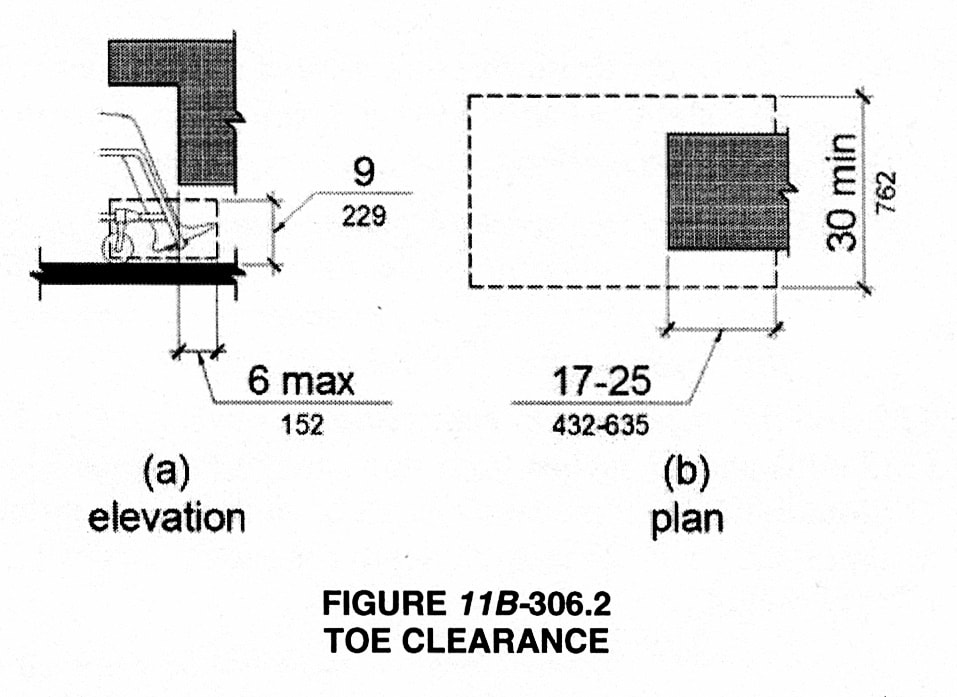

| Although I’m glad to talk about this little phraseological pet peeve of mine, not many people ask me about it, but many DO ask me about the other toe line: The area under a sink or other element that provides space for a wheelchair rider’s toes and foot rests. Here’s the toe clearance diagram from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and California Building Code (CBC): |

And what confuses many people about it is that the toe clearance is 6” max. People ask “Why not give more space for people’s toes?” That’s fine, I say. Toes deserve all the space we can give them. But despite Figure 11B-306.2 (above) looking like a counter or implying a lavatory, the code is referring here to maneuvering space; it’s telling you the depth of toe-level space you can include in the 60-inch “Circular Space” as defined in 11B-304.3.1. (By the way, this is what most people just call turning space…or very inaccurately call “the 60 inch turning radius”. Another pet peeve of mine…that would be a 120 inch diameter!)

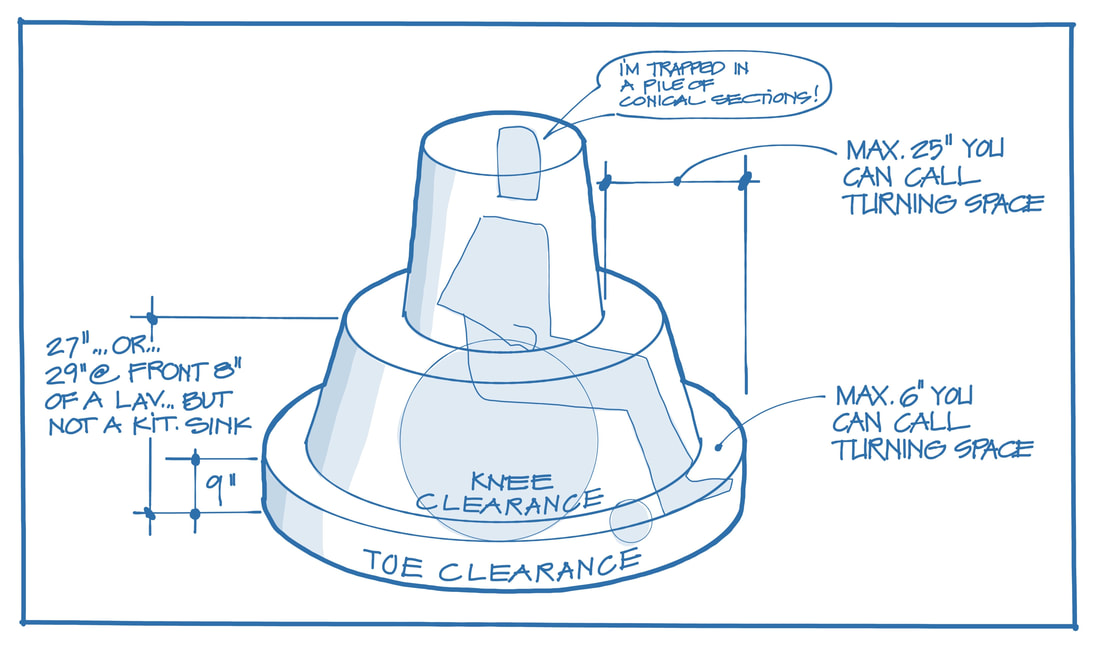

Here’s a diagram that’s more helpful for thinking about the turning space. Imagine this pile of forms sliding in and out of a restroom, kitchen, work areas, etc. That’s where the 9 inch high, 6" maximum depth toe space (and the corresponding 27” maximum knee space height) should be applied.

Here’s a diagram that’s more helpful for thinking about the turning space. Imagine this pile of forms sliding in and out of a restroom, kitchen, work areas, etc. That’s where the 9 inch high, 6" maximum depth toe space (and the corresponding 27” maximum knee space height) should be applied.

The following is how the code describes this in CBC Chapter 11B-306.2.4 (but since there are no accompanying figures, it’s usually overlooked):

“Space extending greater than 6 inches (152 mm) beyond the available knee clearance at 9 inches (229 mm) above the finish floor or ground shall not be considered toe clearance.”

This says "available" knee clearance. In my opinion, if you don't have an obstruction limiting the knee clearance, you can claim more than 6" of horizontal toe clearance.

Bonus Tip: A lavatory is not a sink…

A related confusion is that the CBC differs from the ADA in sinks. We have these two definitions (Chapter 2) in California:

LAVATORY. A fixed bowl or basin with running water and drainpipe, as in a toilet or bathing facility, for washing or bathing purposes. (As differentiated from the definition of “Sink”.)

SINK. A fixed bowl or basin with running water and drainpipe, as in a kitchen or laundry, for washing dishes, clothing, etc. (As differentiated from the definition of “Lavatory”.)

So whereas kitchen sinks and work counters need to have the clearances shown above, a bathroom lavatory in California needs a thinner front edge, to allow for more ability to get in nice and close. To remember this, picture someone in a wheelchair washing their face in the bathroom - they need to get in closer than when they’re reaching out and washing dishes in a kitchen sink.

“Space extending greater than 6 inches (152 mm) beyond the available knee clearance at 9 inches (229 mm) above the finish floor or ground shall not be considered toe clearance.”

This says "available" knee clearance. In my opinion, if you don't have an obstruction limiting the knee clearance, you can claim more than 6" of horizontal toe clearance.

Bonus Tip: A lavatory is not a sink…

A related confusion is that the CBC differs from the ADA in sinks. We have these two definitions (Chapter 2) in California:

LAVATORY. A fixed bowl or basin with running water and drainpipe, as in a toilet or bathing facility, for washing or bathing purposes. (As differentiated from the definition of “Sink”.)

SINK. A fixed bowl or basin with running water and drainpipe, as in a kitchen or laundry, for washing dishes, clothing, etc. (As differentiated from the definition of “Lavatory”.)

So whereas kitchen sinks and work counters need to have the clearances shown above, a bathroom lavatory in California needs a thinner front edge, to allow for more ability to get in nice and close. To remember this, picture someone in a wheelchair washing their face in the bathroom - they need to get in closer than when they’re reaching out and washing dishes in a kitchen sink.

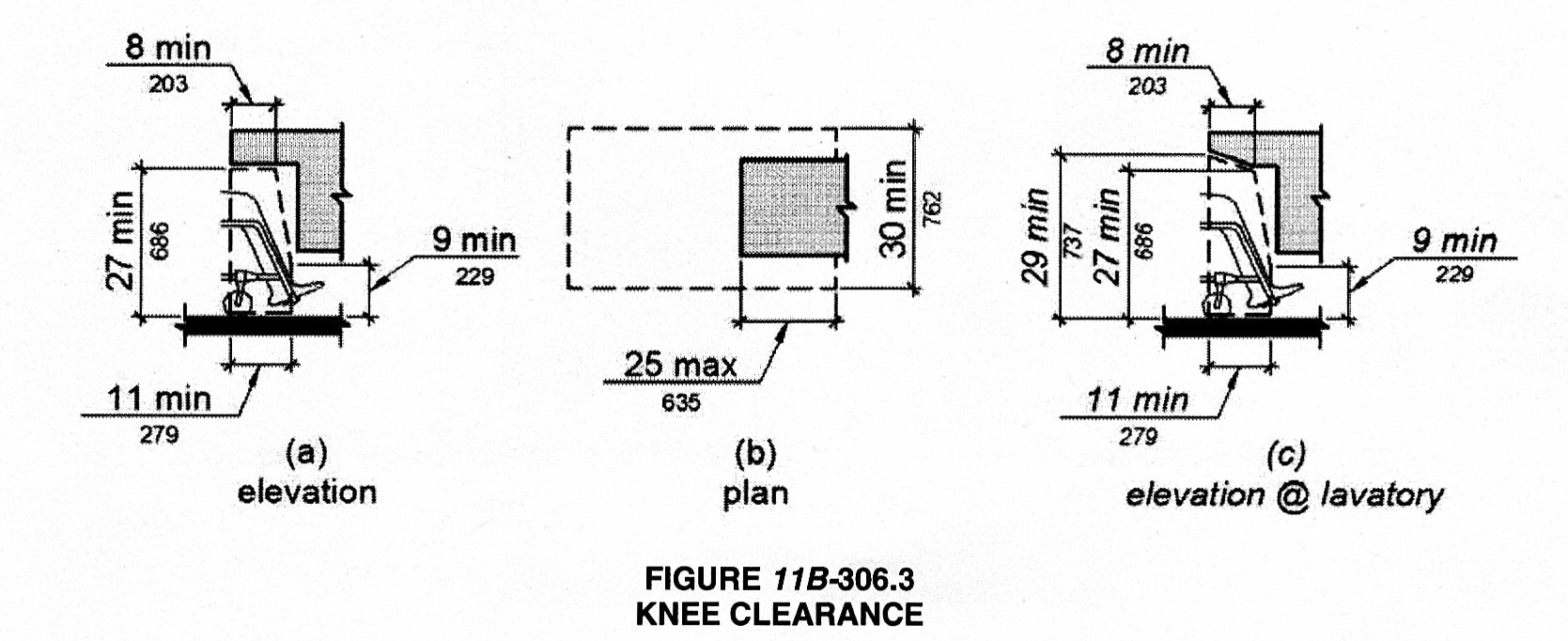

Here’s the CBC figure showing the lavatory toe space requirement - figure (c):

The requirement is for 29 inches clear at the front of the lavatory. Since the maximum top-of-lavatory dimension is 34 inches, this results in a sink that’s at most five inches high at the front. This is a very difficult requirement to meet with a wall-hung sink; probably 95% of the ones on the market that say they are “ADA Compliant” have a front edge that’s over five inches tall. So beware those little wheelchair symbols on cut sheets! They often don’t work in the Golden State!

Duravit, Wet Style, and Barclay have California-complying sinks, and with great contemporary designs to boot (including some by Philippe Starck), and many have drains in the very rear, which is a plus for added knee space:

Duravit, Wet Style, and Barclay have California-complying sinks, and with great contemporary designs to boot (including some by Philippe Starck), and many have drains in the very rear, which is a plus for added knee space:

It’s temping to just do a countertop with a shallow bowl in it to meet the depth requirement. Resist this in high-use public restrooms, because the countertop inevitably winds up splashed and perennially wet. Not only does this look messy, but it’s a nightmare for the sleeves of people using wheelchairs, shorter people, and kids. But if you must, set your countertop below 34 inches so that if the undermount sinks you specified wind up being value engineered out during construction and replaced with self-rimming ones, you don’t wind up out of compliance…the required 34” maximum measurement is to the sink rim, NOT the countertop.

As I always say, we should take any opportunity to provide MORE space than the code minimums require. If you can provide more knee space, then someone in an electric wheelchair with a joystick out front, or someone in a high-seated scooter who pulls up sideways and needs more knee space when they turn their seat 90 degrees is going to thank you. Who knows - that might just be you or a family member one day. So let’s make better, more flexible architecture…and not just toe the line.

As I always say, we should take any opportunity to provide MORE space than the code minimums require. If you can provide more knee space, then someone in an electric wheelchair with a joystick out front, or someone in a high-seated scooter who pulls up sideways and needs more knee space when they turn their seat 90 degrees is going to thank you. Who knows - that might just be you or a family member one day. So let’s make better, more flexible architecture…and not just toe the line.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed