The 14th Amendment and Eugenics

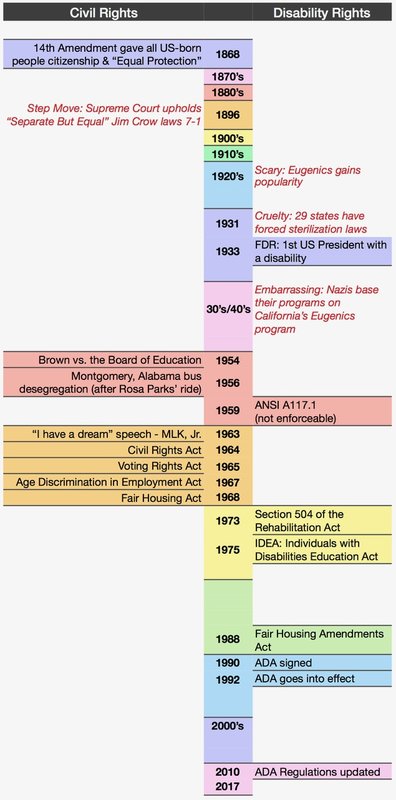

A long and ugly history preceded any legal protection for people with disabilities (see the timeline I put together at the end of the article). The 14th Amendment gave citizenship and “Equal Protection” to all people born in the US…way back in 1868! Yet in the 1920’s, the Eugenics movement spread around the globe. Francis Galton analyzed the intelligence of England’s upper classes and determined that “it would be quite practicable to produce a highly-gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations”.

That might sound innocent, but the Eugenics Record Office in Long Island collected data on “undesirable” physical and intellectual traits, and by 1931, 29 states had sterilization laws that allowed doctors to “eliminate negative traits.” This resulted in the forced sterilization of 64,000 US citizens. It started with people with disabilities, expanding to people committing “crimes” like promiscuity or poverty. No Equal Protection there!

The Civil Rights Act and Class Status

It was 86 years after the 14th Amendment that Brown vs. the Board of Education finally abolished racial segregation in schools, and another ten before the Civil Rights Act gave deeper protections.

One legal legacy from the Civil Rights Act is “Class Status”. This defines a group and enables the government to establish protections for the members. These applied to race, color, religion, national origin, sex…but nothing to people with disabilities.

It wasn’t until 1973, 105 years after the 14th Amendment, that Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act required equal treatment of people with disabilities…but only for federally-funded programs. So for two decades after the Civil Rights Act, people with disabilities could still be legally marginalized. It wasn’t until 1988 that the Fair Housing Amendments Act established people with disabilities as a Protected Class, and laid the foundation for the ADA.

This photo of people protesting against inaccessible public transportation is one of my favorites. One sign reads “I can’t even get to the back of the bus”. Disability Rights protests proliferated, modeled on the Civil Rights movement, with sit-ins, building occupations, marches, and people chaining themselves to buses, demanding equal treatment.

This highlights the Separate But Equal concept that Oliver Wendell Holmes’s Supreme Court in 1896 said was ‘good enough’. The resulting Jim Crow laws formalized segregation until 1954’s Brown vs. Board of Education desegregated schools. And to think…I attended Holmes High School in Texas without knowing this. Ugh.

We all know that civil rights laws don’t necessarily mean real-world equality. Similarly, Section 504 and the ADA didn’t automatically create full accessibility for people with disabilities; equal employment, equal public transportation, and equal facilities in buildings are still lacking. To fix that, we need to first accept the simple reality that everyone’s needs are different, and then agree that it’s not good enough to design some things that are accessible and some that are not. Instead, let’s strive for Universal Design as the ideal, and together we’ll create an environment that is elegantly human and fundamentally just.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed